Romain Clement, cicm

Missionary in Belgium

In August of 1914, the First World War began. Today, we can learn about the events of a century ago through various media. In the upcoming articles, we will discuss the impact of the war on Scheut and, more specifically, on the young Belgians who were studying there at the time. In 1914, these students were primarily located in our Scheut-Anderlecht houses (for novitiate and philosophy) and in the Leuven house (for theology and university studies).

Stamford Hill

In the weeks leading up to the war, approximately 20 young people had already been called up for their militia service, becoming our first "front-line soldiers." When the war broke out on August 14, the remaining students were sent back home, at least those who could still leave. At this point, Superior General Florent Mortier and his Council decided to move to unoccupied territory in order to remain in contact with the various mission areas. Father Mortier took with him the archives of the Congregation and traveled to London. He found a spacious lodging in an unused retreat house of English Sisters, the “Cenacle,” in Stamford Hill, located north of the capital. As soon as possible, Father Mortier invited as many novices, theologians, and professors as possible to London to continue their formation. Meanwhile, the philosophy students moved to Sparrendaal in neutral Holland.

From the beginning of the war, the houses of Scheut and Leuven were equipped and officially recognized as Red Cross emergency hospitals. Scheut would never be used as such; in Leuven, however, many wounded would find shelter until the end of the war.

"The good Sisters put in a great effort to accommodate our community in this edifice. At that time, there were no fewer than 109 of us: theologians, novices, and students. We, unknown strangers, received the most generous welcome in Stamford Hill. In that way, on foreign soil, the Cenacle became like the Motherhouse of our Congregation. It was in Stamford Hill that our jubilee was solemnly celebrated, the ordinations of our priests were held, the poignant departure of our missionaries took place, and our fellow brothers who returned weary and exhausted from foreign lands found a home, motherly care, and a restoration of their strength."

(Testimony of one of the residents of Stamford Hill, published in "Missiën van Scheut," 1920)

Auvours

A military law of March 1915 had significant consequences for our students. All Belgian men between 18 and 25 who resided in unoccupied Belgium were called up to make themselves available to the Belgian army. Of course, many of our students who lived at Stamford Hill or Sparrendaal were included. Religious and priest students were requested to go as soon as possible to Auvours, just north of Le Mans in France. Among other things, a branch of the C.I.B.I. found a place in the spacious barracks of Auvours (C.I.B.I. = Centre d'Instruction pour Brancardiers et Infirmiers - Training center for stretcher-bearers and nurses). Very quickly dozens of young Scheutists settled there. Their preparation for “the front” began. Some Belgian theology students who were not accepted in Auvours went with the Dutch to “Huize Gerra” near Sparrendaal and continued their studies there.

In Auvours, the “cibists” (as they were commonly called) received a solid preparation for the task ahead of them. Camp life consisted of military and Red Cross exercises: marches, theory lessons on the organization of the Belgian army, and practical lessons. Moral and spiritual preparation for front life was also considered. This usually took place exclusively in the morning. There was time for personal study, prayer, and relaxation in the afternoon.

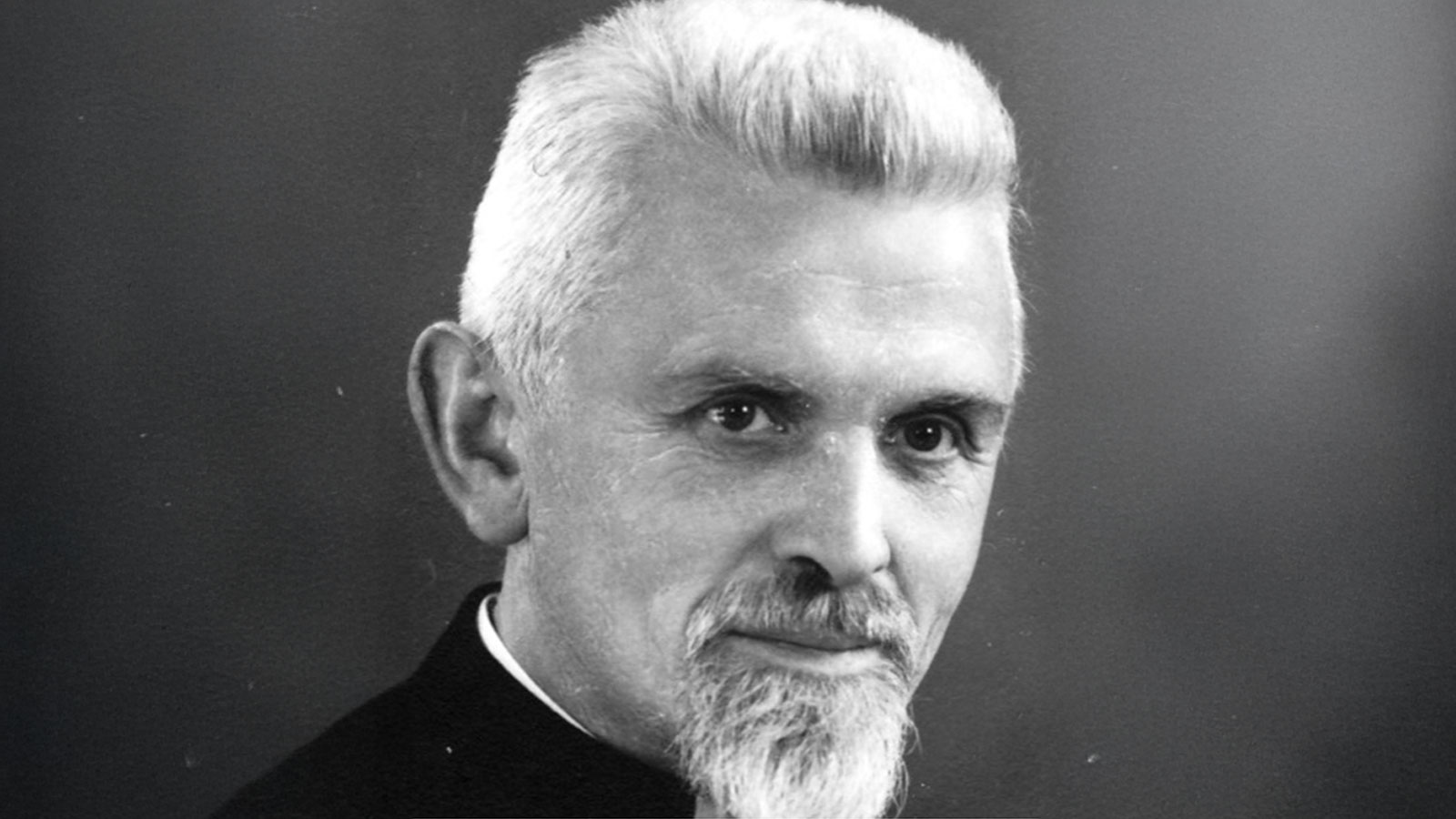

Fatines

Very soon, the Superior General joined his confreres in France. With the help of the local bishop, he could avail of the spacious presbytery of Fatines, a village near Auvours. From there, he served four parishes without a pastor and kept in touch with the cibists of Scheut. Soon, however, he returned to London to continue leading the congregation from there. He was succeeded by Father Albert Gueluy, his first assistant, who temporarily became the superior of the “army Scheutists,” thus including those already working at the front or in military hospitals. The latter maintained a regular correspondence with Father Gueluy. To this day, the preserved letters constitute a very rich source of information about that period.

Every evening, the confreres of Auvours could, if they so wished, go to the presbytery of Fatines for some rest and supper. From May 1916 on, they were even allowed to spend a whole Sunday in Fatines. However, none of that lasted very long because the first cibists left Auvours and were deployed to the front in the summer of the same year. At the end of 1916, everyone would have left, although throughout the war, there was always a certain presence of confreres in the camp, including those who were wounded at the front and needed care.

Scheut in Auvours also had its misfortunes. On September 18, 1915, theology student Karel De Croo died of intestinal infection in the neighboring hospital of Yvré-l'Évêque. The funeral service was presided over by camp chaplain Karel Servranckx, SJ. Shortly after this, on October 13, 1915, Maurice Serulier, who celebrated Mass daily in Yvré-l'Évêque, was accidently hit by a train while crossing a railroad track. He had been ordained a priest on June 29 of the same year. Superior General Florent Mortier himself came over from London to preside over the funeral.

In the summer of 1916, when the first cibists arrived from Auvours, the front line, at least as far as Belgium was concerned, was more or less stabilized around an 84 km long line of trenches extending from Nieuwpoort to Ploegsteert. West of that line were the Allied armies, and east of it were the Central armies.

Life at the front

About 120 Scheutists were assigned to the Allied armies as stretcher-bearers and about a dozen as chaplains. Six postulants (candidate Scheutists) were regular soldiers. The Belgian government did not call up the actual missionaries (in the mission fields, on leave, or ready to leave). A large proportion of Scheutists enlisted in the army were deployed to the front, while others worked as nurses in military hospitals at the rear of the front.

We are all familiar with the classic image of stretcher-bearers: people who venture into the front lines with a stretcher to carry away the dead or wounded. The dead were given a temporary burial place, and the wounded were taken to a field hospital or further away behind the front. It must have been a tremendously hard and risky job. Yet our Scheutists did it (together with so many other religious and seminarians) for two to three years, depending on their arrival at the front.

Stretcher-bearers with a religious background were asked to do more than just take away wounded and administer some primary care to them. Spiritual support was also part of their duties, and this, of course, was also the task of the chaplains. Here and there on the front lines, very simple places of worship – front chapels – were provided that were part of the labyrinth of the trenches. Besides, churches nearby were also available. The stretcher-bearers were supposed to listen to the soldier's daily concerns, encourage them, and share their suffering. They were sources of upliftment amidst the general feeling of depression and moral distress. And yes, dealing with criticism, ridicule, and open opposition from embittered soldiers and their commanders were also part of their task.

Promotion of one's own spiritual life

In connection with their training at the C.I.B.I. in Auvours, we have already mentioned that in addition to preparing them for their task as chaplains or stretcher-bearers, much time and attention was also devoted to maintaining the spiritual life of the young Scheutists. Through the efforts of Father Albert Gueluy and other confreres who resided in Fatines, classes, conferences, and spiritual exercises were organized for the future frontline Scheutists, and the latter had also access to spiritual literature.

In the spring of 1916, as instructed by Superior General Florent Mortier, Fr. Albert Van Zuyt had purchased a house for the congregation, Villa Héloïse in Le Tréport, a town on the French coast between Dieppe and Amiens. Albert Gueluy remained in Fatines for quite some time while Fr. Mortier entrusted the spiritual care of the front-line soldiers to Albert Van Zuyt. Thereafter, the men at the front had to maintain regular correspondence with Fr. Van Zuyt and report, among other things, on their income and expenses. Most of this correspondence has also been preserved and is a rich source of information about the turbulent war period. The soldiers were invited to Le Tréport during their periods of furlough to attain as much outer and inner peace as possible. And they made the most of this! The Scheutists tried to take their furlough, especially during periods of feast days, to celebrate these days in a fraternal atmosphere.

Front-line Scheutists were also encouraged to meet monthly for what we would today call a “recollection”: a talk by one of the chaplains, a reading of a few articles from the Scheut Constitutions, the celebration of Mass, and a meal. The rest of the meeting was spent in “Scheutist revelry”!

Confrere chaplains cooperated as much as possible in the spiritual formation of Scheutists at the front. Not only did they occasionally hold a spiritual conference, but they also rented rooms where the Scheutists in their division could meet and avail of useful books for spiritual reading.

"Once, at the entrance to the church in Hoogstade, a soldier approached me out of breath.

-'Can I go to confession, chaplain?' (every word was interrupted by a sigh, and on closer inspection, I noticed that he was covered with mud).

- 'Sure, boy, come in; there's still a confessor at the confessional on the left.'

- 'Good, because it's terrible.' We came out of the trenches and got shelled by big bombs along the way, more than enough to kill us all. I'm so glad to be out of it. Three guys were killed, several wounded. I threw my bike into the cantonment and walked straight to the church."

(testimony of army chaplain Fr. Jaak Leyssen, see Missiën van Scheut, 1919, p. 183)

Other activities

From Le Tréport, Albert Van Zuyt, in collaboration with several chaplains, began the publication of a front magazine for the Scheutists. The first issue appeared in June 1916, and the last in July 1918. The first title was “The Scheutist and later became “C.I.C.M.” Chaplains wrote articles in the gazette, and young people at the front were also invited to send some news from the front to Le Tréport. The gazette was distributed at 125 copies.

Some frontline Scheutists extended their activities to give simple instructions to ordinary soldiers, such as learning to read and write and lessons in French or Dutch. Still others founded choirs or drama groups.

For any mutual gathering, the Scheutists were always welcome at the Blue Sisters in De Panne and in the house of the mother of Edmond Devloo (in his turn a temporary frontline Scheutist) in Oostvleteren. The Devloo family sent us a picture of such an informal meeting. We are pleased to publish the picture. Edmond himself is sitting on the far right. On the back of the photo, someone wrote “1916.”

The Belgian newspaper "De Standaard" of March 18, 1919, had the following text: “We used to know our missionaries only by hearsay; their field of work was far from here. The war, however, brought them into our midst. We saw them working in our ranks and on our own soil on a mission field—a battlefield.” So wrote “The Standard” on March 18, 1919.

The end of the war

When the final offensive against the central forces got underway in the summer of 1918, four Scheutists had already died. The first two – Karel Decroo and Maurice Sérulier – killed at Yvré-l’Evêque in 1915, have already been mentioned when talking about Auvours and Le Trépont. Two others died a few months after they enlisted in the army: Kamiel Trap and Hector Vandeputte. Eugeen Requette died in 1919 at a Rouen hospital due to injuries sustained. During the final offensive itself, other stretcher-bearers died: Leonard Dirckx, Herman Chielens, Karel Rathé; Gaston Devel and Paul Impe both died at Houthulst on September 28, 1918; Gervais Toussaint died on October 9, 1918; and finally three more men died in November, during the very last days of the war: Jan Cops, Jozef Tirez and Frans Maes, the latter on November 10, one day before the armistice. Also, about 30 stretcher bearers were seriously or lightly wounded.

That was the sad balance sheet of the participation of about 130 Scheutists in the war as stretcher-bearers or chaplains. Bishop Jan Marinis, in charge of the entire army sector since September 1915, afterwards praised the Scheutists who had participated in the war. The army authorities in their turn seemed satisfied, given the many military decorations bestowed upon our confreres.

The demobilization

It is not so that after November 11, 1918, all confreres could return immediately to their study houses. First, all stretcher-bearers were assembled in the C.I.B.I. of Veurne and, from there, deployed to various military hospitals in the former front region to care for the wounded. In May 1919, this changed. Part of the former stretcher-bearers were temporarily stationed in a "center for military students" in Brussels, another part in Leuven. The first group could then follow the novitiate or philosophy training in Scheut; the others could continue their theology in our house of Leuven. However, they all remained soldiers and thus had to appear in uniform each time. Finally, in August 1919, the general demobilization followed.

New adaptation to monastic life

First let us go back in time for a moment. In September 1915, the Congregation had again begun accepting novices under the leadership of novice master Fr. Arthur Surmont. Each year, those novices naturally moved up a year: first to philosophy, then to theology. This meant that by the school year 1918-1919, our study houses at Scheut (novitiate and philosophy) and Leuven (theology) were again occupied. Suddenly, a whole group of former stretcher-bearers, who had to interrupt their studies in 1915, joined them at all levels. It could be foreseen that problems would arise!

It must have been extremely difficult for the ex-soldiers, after years of confrontation with the violence of war and deep physical and moral misery at the front, to assimilate into a monastic discipline that they were no longer used to. They had to bend to the wishes of those in authority who usually had little or no experience of war conditions. They had to conform to the rhythm of a monastic life that had become foreign to them. A regular and intense prayer life was on the program; the study life had to be arranged to perfection, silence had to be maintained, and politeness had to be imposed. And then, as just mentioned, there was the fact that from now on, they had to share life with other young people who had only known the war from a distance and sometimes felt somewhat “overwhelmed” by these often rough newcomers

A positive element in all this, at least as far as the house of Louvain was concerned, was that the superiors of the Congregation had appointed Father Albert Van Zuyt as their rector. Through the front soldiers’ visits to Le Tréport and their regular letters, Father Van Zuyt knew them well. Thus he was the ideal man to be an encouraging and conciliatory factor in an often tense situation in Leuven.

"If the task of our confreres was varied and difficult, all the greater is their joy and happiness now that they have all returned to our midst, satisfied with the work done. Steeped in their working power, they are now preparing in our houses of Scheut and Louvain with new zeal to fight paganism on foreign soil one day."

- Fr. Jaak Leyssen in "Missiën van Scheut,"

The strict movement

There has always been a tension within the Congregation between the religious and missionary aspects of the Scheutist vocation: is a Scheutist first and foremost a monk or a missionary? This tension reached its peak, especially in the years following World War I. A great deal has already been published on this subject, so we will limit ourselves here to a few isolated observations.

Those who especially emphasized the religious element – the adherents of the “strict movement” – liked to refer to Fr. Arthur Surmont as their pioneer. The latter had been a novice master for 19 years, from 1919 to 1930, and had clearly left his mark on the young people of that time, thus also on many young people whom the ex-soldiers met in Scheut and Leuven. For the latter, this constituted an additional problem in addition to all those mentioned above. However, Father Van Zuyt and a few professors, including Fr. Jozef Calbrecht, could also play a conciliatory role. However, this did not take away the fact that about 20 ex-soldiers left the Congregation shortly after the war. Others, however, grew into energetic and courageous missionaries.

https://www.cicm-mission.org/index.php/en/reflections/45-in-the-frontline/621-scheut-and-the-first-world-war#sigProId6e67b6e97f