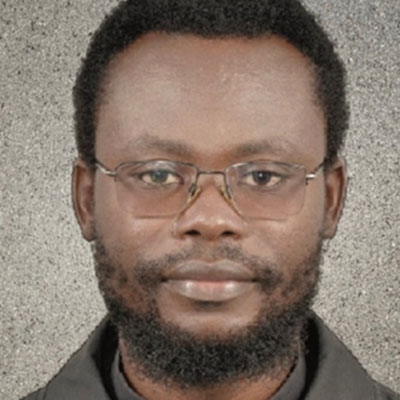

Jacques Brui

(1933-2022)

Born in Mouscron (Belgium) on June 5, 1933

First vows on November 1, 1959

Perpetual vows on

He was a missionary in Congo (Kinshasa) and in Belgium

Died in Anderlecht (Belgium) on October 29, 2022, at the age of 89.

Jacques used his words sparingly. He never said a single excessive word. He would frequently respond to questions with a single word. Jacques Brui (brui means noise in French) was often teased for not making much noise. But his mimics spoke volumes. When people expressed concern about him or his health, one of his favorite expressions was “T’en fais pas,” which translates as “don’t worry (about me).” Jacques did not want to be a burden to anyone, he did not want to be looked after, and he did not want to be the center of attention. He didn’t ask or request anything for himself. Even on his birthdays, he preferred to keep them private. The last few months were especially difficult for him because he became dependent, which was contrary to his personality.

Jacques’ missionary journey path was almost perfectly straight, with no detours. As a professional accountant, he applied his skills with competence and rigor in the service of various Treasurer Offices and Procures, caring for the good of the confreres and the Congregation, and was concerned with reliable management as a good father. He despised squandering. He never took a vacation, and even when he visited his family in Canada, it was for work. His hobbies included stamp collecting and tending to the flowers in the garden on Rue Berckmans.

When his work was completed and the Treasure Office was handed over, Jacques could have taken a well-deserved rest. However, he volunteered to serve patients and visitors at the Edith Cavell Clinic in Uccle. After the somewhat austere work in the Treasurer’s office, Jacques enjoyed volunteering at Cavell. He had fond memories of discovering new youth among the nursing staff, particularly females. A service he dedicated himself to for 15 years. He was happy to talk about it because it made him feel useful and appreciated. When he mentioned his good relationships with the nurses, I would gently reprimand him, “Jacques, this is not your age anymore,” and he would smile. The icing on the cake was that he could collect uncancelled stamps or batteries that were still usable and bring them to Scheut. The details were important to Jacques. There are no small savings. It was his way of helping the environment.

We first met almost 50 years ago at Kinshasa’s Scopenko (Father NKongolo Scholasticate). Jacques was the Treasurer, and I was studying Lingala. I frequently reminded him that he had entrusted me with the community store, that is, the small store with a few essential products for the boarding students’ group that we were forming. I teased him, saying how much I appreciated his trust in me, a stranger. It was the beginning of a complicity that would last forever.

I spent the majority of my successive vacations at Rue Berckmans, where I ran into Jacques, who was faithful to his position as Provincial or Local Treasurer. Jacques was a reference on the Rue Berckmans. When he moved to Anderlecht, I began calling him ndoyi (my namesake), an affectionate title he accepted willy-nilly. I could tease him as much as I wanted. He never took offense because teasing was part of our ndoyi relationship’s familiarity, in a context of mutual trust and respect, of recognition for all he had been. He knew I accepted him, with all his flaws. When I was worried about him or his health, how many times did he say, “T’en fais pas.” In reality, despite appearances, he was a compassionate person, and teasing was an informal way of communicating with him and keeping him in the loop.

“T’en fais pas,” he said the last time I visited him in the hospital two days before he died. They were words of assurance and peace. Don’t worry about me. Jacques knew he was in good hands because he had entrusted his life to the One who had been his faithful companion throughout his religious and missionary life.

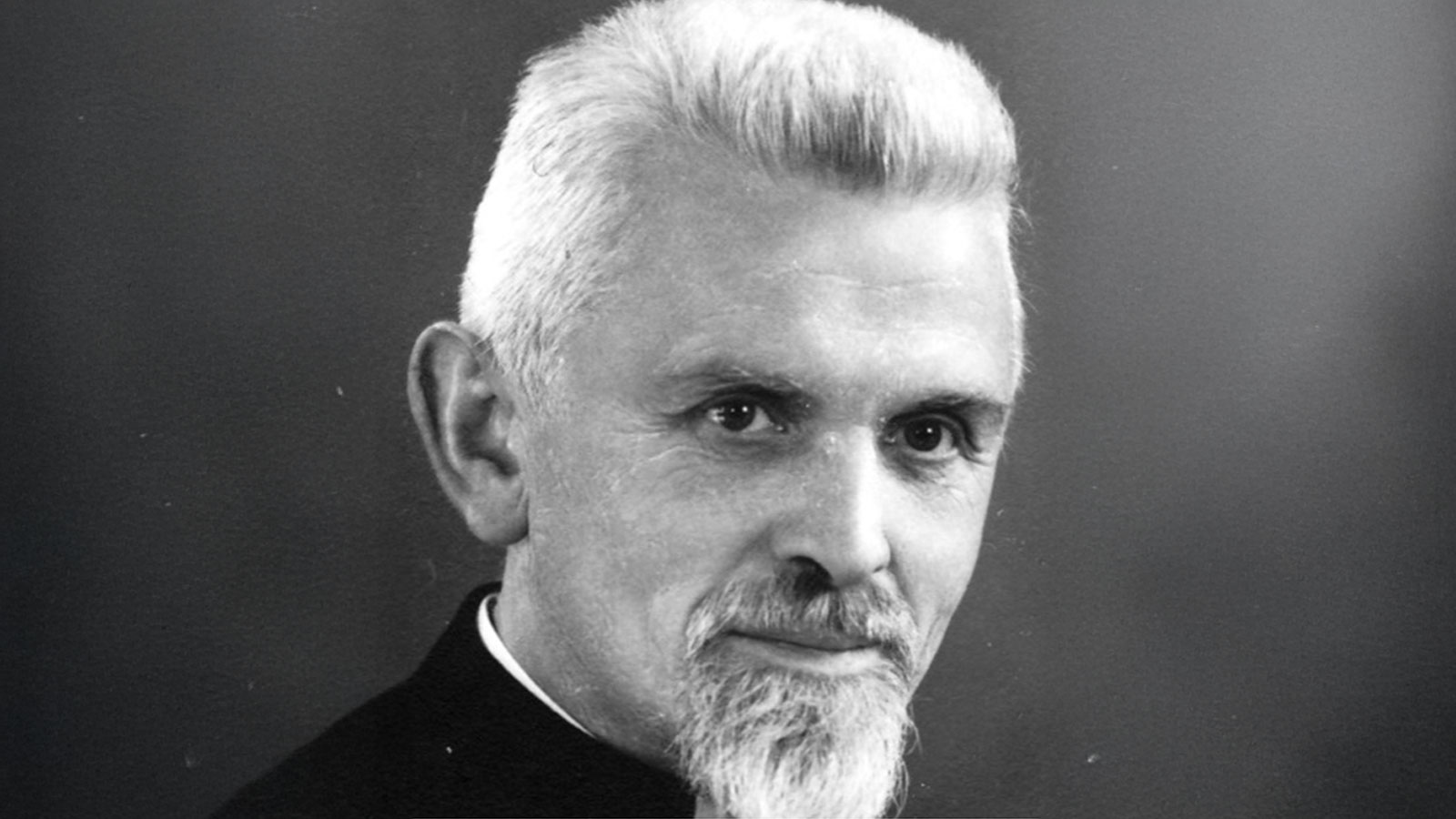

Jacques Thomas